8:44pm. It’s 83°outside. I’m twirling in a hyper-flowy crochet dress on my parents’ driveway, my baby cousin, N, recording me on her iPhone saying, “You look really good, Manang!”1 It’s been an exhausting weekend: on Saturday, my parents, my husband, W, and I hosted one of the most saddest events in any of our lives —my younger brother, D’s memorial. A huge portrait of him rested at the foot of the church pulpit, flanked by bouquets of white flowers and his sea blue urn covered in ti leaves. It was the only time I saw W collapse in tears since the moment we heard about D’s untimely death back in June. The sight of this unreal scenario, my brother’s soulful gaze frozen in time, brought the reality of his death crashing down on my poor husband, bringing him to his knees.

We then had only a couple hours after the reception ended before heading to one of D’s bff’s tattoo shop for a late night gathering with friends and cousins. The mood of this get together was infinitely lighter (and filled with alcohol). New relationships were built, memories were shared, cigars were smoked. W reprised his eulogy with another toast to D that sent the packed shop into wild cheers: “Cheeeee-hoo!”

Then midnight rolled around. Friends with families or early morning flights bid their farewells, exchanged phone numbers with the promise of staying in touch. As default designated driver (W wasted no time in tossing back shots), I commandeered W’s Prius back to my parents’ house. We needed rest before brunch the next day. And little did we know it, but after brunch we would make an impromptu visit to D’s other bff’s house for his son’s 15th birthday. Cue more alcohol, Cambodian jam sessions, and tri-tip steak. I enjoyed meeting his parents, too. A pair of gregarious and loving yet hard-nosed people if I’d ever met any. And we can’t forget the group of drunk nurses congregating in the backyard, teaching each other how to insert IVs.

The Walk

8:41pm. W and I are back at my parents’ from the birthday party. Despite the exceptionally warm summer evening, someone in my family suggests a walk toward the lake behind my parents’ house. Under the cover of darkness, about eleven of us venture out into the night. While I enjoy my private performance in the aforementioned crochet dress, my cousins C and M race to the end of the street, savoring the warm summer breeze whipping through their hair, the sound of their flip flops smacking deliciously against the asphalt. Even though we are months past the summer solstice, the sun hasn’t completely set. A sliver of sunlight outlines the gently rolling hills, now black silhouettes against an indigo sky. The dirt roads are barely lit, rendering people’s bodies as mere shadows in the dark. Some dance, some skip, some run as we traipse onward.

Under the cover of darkness, C and his wife K enjoy a moment lost in each other’s eyes, her belly swollen with life. As our miniature collective tries to shrug off the heavy emotions of grief and sorrow, it dawns on me how arbitrary this thing called life can be. While we mourn the loss of my brother, we also wait in anticipation for new life to be born. We have two pregnant couples in the family and my baby nephew, Z, just celebrated his first birthday.

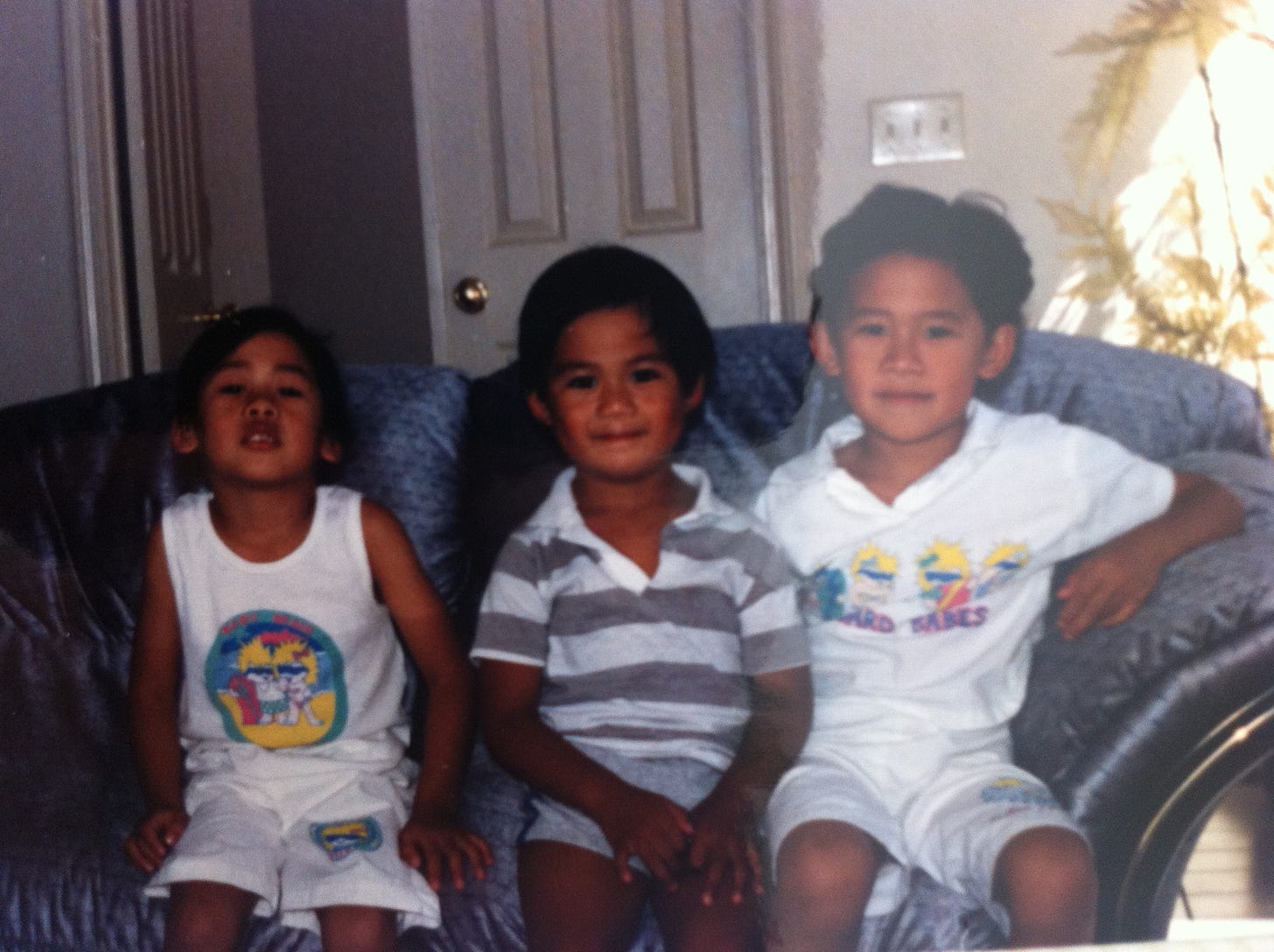

On the other side of that coin flip Death lurks. W and I have been to more funerals than we’d care to admit, many of whom were some of our favorite people. In 1999, my cousins R and J, brothers, died almost instantly in a car crash at the tender young ages of 17 and 16 years old. My brother joins them decades later, our angels, taken early and unexpectedly from this earth.

I have to remind myself that I’m not the only one who has experienced loss. In a moment that flashes before my eyes, I see the faces of people I’ve worked with in my career as a psychotherapist. The women who have gotten abortions, or had miscarriages. The grown adults who grieve the loss of innocence as a result of childhood abuse and neglect, of addiction and substance dependence. The parents and families, whole communities who’ve been ravaged by senseless mass shootings. The list is endless. And it occurs to me that we are all connected by this common thread of human suffering.

In my own minute corner of the world, my loss feels monumental, unreal, like a nightmare come alive. But to the universe, it is but one of many deaths that maintains the balance of our spiritual and natural ecosystems. Somehow, I find it comforting to perceive my loss as a small happenstance on this epic stage of Life. It means I’m not alone even when it feels like I am. It means I may not have been the only one targeted to endure this cruel game of chance. Underneath the shiny veneer of social media, reality TV, and next-day shipping, perhaps Life doesn’t have to be the lonely journey existentialists make it out to be. Because Death doesn’t discriminate; it comes for us all, anytime, anywhere.

A couple yards behind me, my aunt frets anxiously about snakes in the grass.

Under the cover of darkness, cousin L eagerly requests a group selfie. We squish together in front of her phone and make ridiculous faces into the camera. People may find this odd, but something I noticed in my family is the tendency to smile for pictures and have gatherings that feel almost celebratory surrounding the death of a loved one. I don’t know if this is an instinctive coping response to grief (i.e., denial), or part of a cultural tradition to connect with community during devastating times,2 or both. My mom’s side of the family calls it “bonding time.” Back at the house, L shows me the group selfie as a Boomerang; an extra silly portrait for an extra difficult occasion.

Bonding Time

Under the cover of darkness, the elders gather in my parents’ backyard. It’s eerie, seeing them sit in a circle in the pitch black of night, momentarily punctuated by the motion-sensor light next to the sliding door. It looks like a cult meeting. They inform us grandkids that they’re talking about parenting styles, but I wonder if they share an unspoken fear, a fear that only my grandmother dared utter: that our family is cursed. Old Filipino superstition! one might say, but the evidence is damning. Every family member we have lost on my mom’s side has been tragically young, from my 16-year-old cousin to my grandfather in his late 40’s. The elders sit around and drink beer and casually discuss the facts of life while the darkness conceals a deep mortal fear for our descending lineage.

D’s death is particularly earth-shattering. Widely known to his friends and family as one of the healthiest people we know, my brother pushed his exercise regimen to athletic standards, became vegan, and embodied the positive thinking that would put Joe Dispenza to shame. As far as we knew, he had a clean bill of health. So when news spread that his heart simply stopped in the middle of a typical workday, the shockwaves that reverberated throughout our community were endless. And we are still reeling to this day. If death can come for someone as young and healthy as D…none of us are exempt.

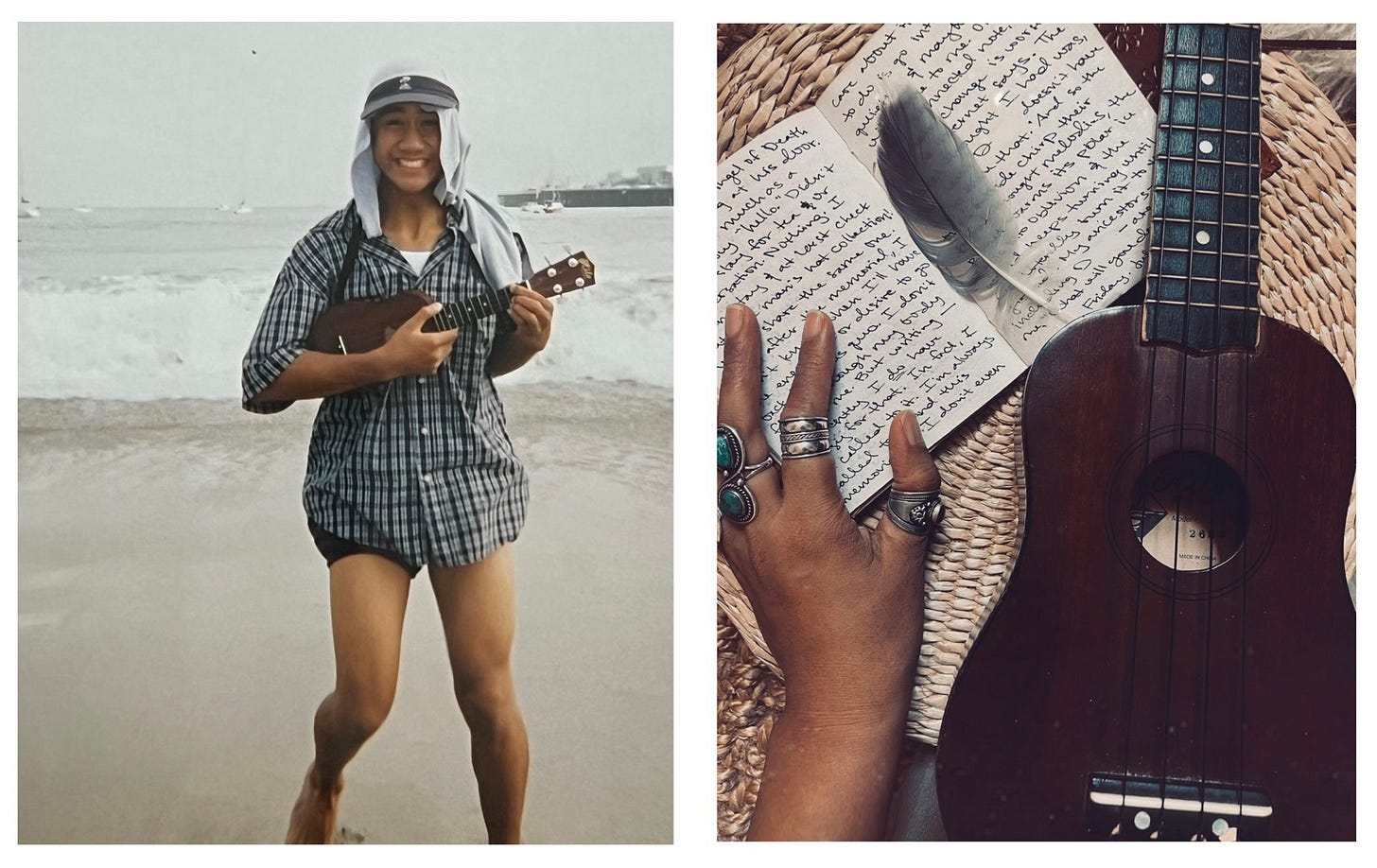

Back in the livingroom, us grandkids have our own bonding time. My parents’ house is filled with guitars and ukuleles, two of which belong to L and C. We search our memories for songs that D used to play. Bob Marley’s “Is This Love” and Extreme’s “More Than Words” are favorites. We sing our hearts out while the younger grandkids film us on their iPhones. As kids, we sang wildly and with abandon, carefree and innocent, sprawled in the back of my uncle’s gray pickup while belting 90’s R&B lyrics into the night wind. This time it’s different. A heaviness weighs on our voices, tinged with the inevitable fatigue of grief and maturity. But still, C patiently demonstrates for us simple chord progressions. Still, I clumsily strum out “Is This Love” on the ukulele.

Still, we sing under the stifling cover of darkness that is Grief.

Before W and I retreat to my room for the evening, I gently trace the black strings on the ukulele I was playing. It’s a cheap, $10 thing from some swap meet or tourist shop in Hawaii. I think it was my brother’s first one. I take it with me upstairs and place it on my suitcase, ready to bring home.

—a. v.

Manang = In the Iluko language, it means “older sister,” or is used as a sign of respect when addressing an older female who is not an aunt, mother or grandmother.

I first heard about a fiesta state of mind from a musical number by the same name in the Fil-Am play, “On This Side of the World.” The lyrics go something like: “You think it’s pretty odd when / We’re feeling all downtrodden / To say that life is going right. / And when the scarcest of resources / Our recourse is / To blow it on a carefree night. / But we’ve had 400 years / Of colonization / Poverty, pollution, extorting populations / Earthquakes, typhoons, volcanic eruptions, corrupt politicians / And fiesta’s got us by.”